- Home

- Flights

- Balloon Instructions

/Information - LANDOWNER FAMILY:

- Special Thanks to The Tomovich Family

for allowing us to celebrate

the 75th Anniversary

of the 1st Stratospheric Balloon Launch

in their backyard.

PILOTS:

Captain-Crystal, Owner/Operator of Morning Star Balloon Co.,

Granddaughter of Kenneth George,

who crewed for Explorer I and Explorer II,

from Amboy WA

nestled at the base of Mt. St. Helens

Mark West, former Aerostar President & Balloon Designer

and new Chief Technology Officer

for Raven Industries

Sioux Falls, SD

Kay West,former First Lady of Aerostar,

Owner/Operator of Prairie Sky, Inc. -

self proclaimed De(va) and Event Organizer

Sioux Falls, SD

Heather Day, Day Weather - 1st Flight

of their balloon "Day One"

was originally from the Stratobowl

Cheyenne, WY

Peter Cuneo & Barbara Fricke, World renowned gas balloonists

and all around great people from

Albuquerque, NM

Dave & Denise Christensen, Flying family with twins

back for a return engagement

in the sport of ballooning

with much enthusiam

after 20 years hiatus

Sioux Falls, SD

Gary Palmer, The Old Brit from South Dakota

(I think that says enough)

Yankton, SD

Bob Kross, Flight Nurse (in case we need one)

and avid sport pilot

Rapid City, SD

Damian Mahony, Flies 315,000 cu. ft. balloons

for Orlando Balloons -

wants to trade swamp for mountains

as a ballooncation (gets the long distance prize)

Orlando, FL

Keely Wade, Private Pilot who follows Damian's 315K

with her 54K over the swamps -

Mark & Kay's daughter

(West meets East Coast)

Ortlando, FL

HIGHLIGHTS FROM SEPTEMBER

24-26, 2010

Celebration of the 75th Anniversary

The First Space Race

by Captain-Crystal

The race for space started long before the first Russian satellite entered the outer sphere in 1959 or before the United States placed man’s first footstep on the moon in 1969. In the early 1930s the race for space was global. Entrepreneurs, private citizens, and governments were all vying to be the first to fly the highest in the atmosphere. Many succeeded… some perished.

All who ventured aloft were voyagers with the same idea…to fly the highest and use the data in order to study what we could not see or touch…the stratosphere. These people were visionaries and explorers, pilots and scientists, men of means and of the press who had the vision that space was (to coin a phrase) our final frontier.

Gas ballooning to the atmosphere was always a dream for the early Aeronauts.

FIRST ATTEMPTS

On July 18, 1803, French Physicist Etienne Gaspar Robertson and music teacher Lhoest launched their gas balloon at Hamburg, Germany to 23,900 feet (7,285 meters). In 1839, English Aeronaut Charles Green and astronomer Spencer Rush rose to 25,918 feet (7,900 meters).

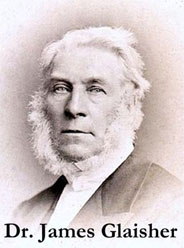

On September 5, 1862 English aeronaut Henry Tracey Coxwell and English meterologist Dr. James Glaisher (known for his publication of the dew point tables for the measurement of humidity) rose to 39,000 feet (11,887 meters) before losing consciousness due to low air pressure and cold temperatures of -11 degress Celcius (12 degrees Farenheit). Dr. Glaisher became insensible due to lack of oxygen during the flight and Mr. Coxwell was unable to use his frost-bitten hands and had to open the gas valve with his teeth in order to descend, although rapidly, back to earth.

In April 1875, Frenchmen Gaston Tissandier, Joseph Croce-Spinelli, and Theodore Sivel reached 28,215 feet (8,600 meters). Both of his companions died from breathing the thin air. Tissandier survived, but became deaf.

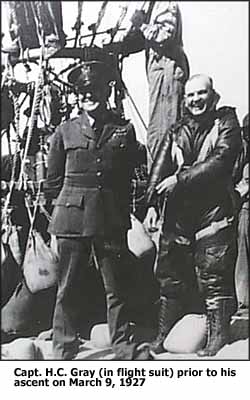

On March 9, 1927 Captain Hawthorne C. Gray, of the U.S. Army Air Corps, ventured aloft in his 70,000 cubic foot single ply, rubberized silk envelope . He set the first U.S. altitude record at 29,000 feet (8,839 meters) on the first of his three flights into the stratosphere.

On May 4, 1927, he attained the altitude of 42,470 feet (12,945 meters) on his second flight, but this was not officially recorded since he had to parachute from his gondola to save himself.

On November 27, 1927, Captain Gray's third attempt into the stratosphere gave him the opportunity to test high-altitude clothing, oxygen systems, and instruments as well as set a new record. He reached 42,000 feet again, but ran out of oxygen on the descent. He arrived on the ground with his balloon, but he was dead. It was the last high-altitude flight in an open basket. This led to the enclosed gondola introduced by leading cosmic ray investigator and Swiss Professor Auguste Piccard.

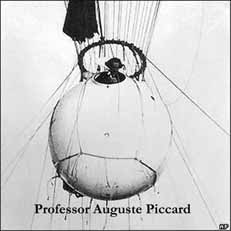

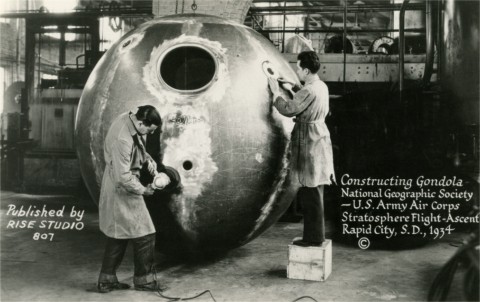

Professor Piccard designed a gondola sphere which weighed 300 pounds, was 82" in diameter gondola, and built to keep two people alive for up to 10 hours above 40,000 feet. The apparatus designed to release pure oxygen into the cabin while scrubbing and recirculating cabin air by filtering it through alkalai was fashioned after the German invention. Professor Piccard also solved the problem of the hydrogen leaking while expanding during ascent. He surmised an envelope five times larger would allow the expanding gases to remain inside the envelope as it reached the stratosphere. This would also allow the two aeronauts to return safely to earth as the gas cooled at night. He then built a 500,000 cubic foot hydrogen filled envelope. This envelope allowed the lifting gas to remain inside the balloon envelope as it expanded, giving the balloon enough boyancy to return safely to Earth as the gas cooled at night.

On May 27, 1931 Swiss Professor Auguste Piccard and Paul Kipfer flew their pressurized capsule and 494,400 cubic foot envelope from Ausburg, Germany and reached a world record altitude of 51,783 feet (15,787 meters). Unfortunately, the balloon landed on a glacier where it was left for nearly a year. this project was funded by the FNRS (Funds National Research Scientific) and King of Belgium who was the foundation's patron.

In 1932, Professor Auguste Piccard and Max Cosyns reached 53,152 (16,200 meters) feet into the stratosphere.

Now the race for space began to heat up as each country had a viable vehicle to travel to the stars. Yes, it was still with risk but the success ratio was now much higher with the invention of the enclosed gondola.

SOVIET'S MISSION

The Soviet Union invested the most time and energy to the discovery of the stratosphere. Since the idea first arose in 1932 by Vladimir Chizhevsky, many gas balloon attempts and actual flights continued until 1940, most under the leadership of Georgy (Yegor/George) Alekseyevich Prokofiev.

On September 24, 1933, the Soviet Union, inspired by Professor Piccard's success and under the command of Georgy Prokofiev, widely publicized the maiden flight of USSR-1 which ended in failure. First, the bottom of the envelope twined itself with ropes during inflation. A volunteer named Fyodor Tereschenko untied the knots, and the balloon was cleared to launch. However, it failed to lift off due to moisture build up in the foggy weather.

On September 30, 1933, the Soviet Union launched USSR-1 once again under the command of Georgy Prokofiev, Konstantin Godunov, and co-pilot/radio operator Ernst Birnbaum. This was the largest balloon built to date at 860,000 cubic feet and the three man crew reached an unofficial record 62,336 feet (19,000 meters). Later that same day, Osoaviakhim-1 was being prepared to launch. However, strong ground winds at the time of launch cancelled the second balloon launch which was rescheduled for January that next year.

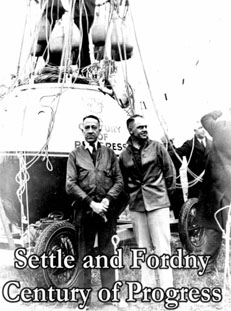

On November 20, 1933, the U.S. team of Lt. Commander G.W. Settle (US Navy) and Major Chester L. Fordny (US Marine Corp.) flew the Century of Progress (a 60,000 cubic foot hydrogen-filled balloon built by the Goodyear Company) to an altitude of 61,237 feet. Rumor was that Josef Stalin, apparently irked by the Settle-Fordny achievement, allegedly would order three Soviet balloonists into the air and to their deaths in an attempt to break the Americanheld record.

And on January 30, 1934 a Soviet Union three man team launched their balloon Osoaviakhim-1 and attained an altitude of 72,200 feet (22,006 meters), beating all high altitude records. Unfortunately, the balloon lost its bouyancy during the descent, plunged into an uncontrolled fall, and disintegrated in the lower atmosphere. The three crew members, probably incapacitated by high g-forces produced by the rapidly rotating gondola, failed to parachute to safety and were killed when the capsule impacted the earth.

In May of 1934, USSR-2 with a 984,252 cubic foot envelope was designed for a two man team. The envelope material was changed to a parachute grade silk in which Prokofiev and Godunov where to fly. On September 4-5, 1934, the filling of hydrogen into the silk fabric caused a static spark and an explosion and fire commensed. No fatalities resulted from the event, but it did shelve the project indefinitely for this type of fabric.

In 1935 USSR-1 Bis was built to replace the failed flight of Osoaviakhim-1. Because the lines failed at an altitude where parachuting to safety was not feasible, the gondola was engineered to more stringent safety precautions. The designers focused on assuring crew survival above 26,246 feet (8,000 meters). USSR-1 was re-fitted with new suspension with a quick release latch that enabled instant separation of the gondola from the envelope, and a large parachute (1,000 square meters, 34 meters diameter) capable of stabilizing the fall at safe speeds. This upgraded aircraft was renamed USSR-1 Bis. With military flight commander Christian Zille, co-pilot Yury Prilutsky, and science officer Professor Alexander Verigo, the balloon launched on June 26, 1935 and flew to 52,493 feet (16,000 meters). Prokofiev was in charge of ground control. A faulty valve produced an unexpected descent. When the vertical speed passed the safety limits producing a likelihood of a crash similar to the previous Osoaviakhim-1, ballast was jettisoned in order to slow the descent rate. This lasted for a short time when the speed picked up again. Zille ordered both Prilutsky and Verigo to parachute to safety. He stayed onboard to lighten the load and brought the balloon to a soft and safe landing.

The next development by the Russian team was USSR-3 with a 515,092 cubic foot envelope. By now, it was noted that weather played a significant part at the time of launch. This was solved by the American teams who were using deep canyons (Stratobowl, SD) and mining pits (Crosby, Minnesota) to stem the flow of wind over the balloon, especially during hydrogen inflation. Because the lines were tangling with the balloon envelope prior to launch, Prokofiev designed a "double launch" sequence. The first test pilot was killed and later it was discovered this would be the traditional problem with subsequent balloon flights.

On September 18, 1937 the newly redesigned USSR-3 launched with Prokofiev, Krikun, and Semyonov using the double cable launch process. The balloon rose to 2,297 feet (700 meters) when the ropes failed to become disentangled and damaged the gas release valve. The balloon rapidly descended and the three man crew had no time to parachute to safety and suffered internal injuries on ground impact.

On March 16, 1939, the last flight of USSR-3 ended the same. Plaqued with the line entanglement issue, the ground team failed to release the balloon from the safety net. Two cloudhopper balloonists (single seat balloons) rose on lines to untangle the net. At 3,937 feet (1,200 meters) the valve opened once again, causing the balloon to crash in the woods nearby. The three man crew survived with serious injuries. While Semyonov and Prilutsky bailed from the gondola, Prokofiev stood on the open top hatch to the end. He was at first reported uninjured. However, examination revealed two shattered vertebrae, feet, and intestinal injuries. It was a surprise when, after Prokofiev was planning on future record flights for May of 1939, that he fatally shot himself.

THE RACE CONTINUES

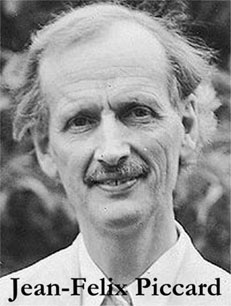

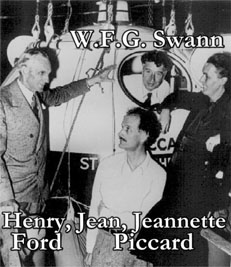

In 1933, Goodyear and Dow Chemical sponsored Dr. Jean Piccard's Century of Progress gas balloon design. The new magnesium and aluminum alloy made the gondola lighter but more more fragile. Now the U.S. was back in the race. However, due to Dr. Piccard's lack of a pilot certificate, Lt. Commander G.W. Settle of the U.S. Navy was scheduled to operate the aircraft to the stratosphere with Dr. Jean Piccard as science officer. As with all races, this one was filled with political agendas and since Settle was the Navy Inspector for Goodyear, rumor is he convinced the board to dispense with Dr. Piccard on the flight and fly alone. As history has shown us, a gas balloon of this magnitude, with instrumentation for scientific exploration, is a two person endeavor.

With 7 hours of ceremonies and parades presented by the Centennial Commission and U.S. Navy for a crowd of 40,000, Lt. Commander Settle launched the 15 stories tall, 600,000 cubic foot Century of Progress from Soldier Field in Chicago, IL on the dawn of August 4-5, 1933.

This was to be the first of three stratospheric attempts by the Century of Progress. Ten minutes into the flight, a leaky valve began to release hydrogen from the envelope. This was due in part from issues pertaining to the weight of the valve cord and the bottom part of the fabric. After a short flight to 5,000 feet (1,524 meters) Lt. Commander Settle landed in a local railroad yard, surrounded by a crowd of hundreds. It was reported the large, riotous crowd hampered with authorties in safeguarding the aircraft with one bystander critically injured. This included people smoking on and around the partially filled hydrogen gas bag.

With a call from the U.S. Navy to retrieve their balloon, the Piccards assembled a group to pack the balloon and gondola and transfer them to a local auditorium to dry. Later, Lt. Commander Settle would be loaned the use of the Piccard's Century of Progress for his second attempt at breaking the altitude record.

On November 20, 1933 Lt. Commander G.W. Settle (U.S. Navy) and Major Chester L. Fordny (U.S. Marine Corp.) flew the Century of Progress to an altitude of 61,237 feet (18,665 meters). Headed once again by Dr. Jean Piccard, it carried two instruments to measure how gas conducted cosmic rays, a cosmic ray telescope, a polariscope to study the polarization of light at high altitudes, fruit flies to study genetic mutations for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and an infrared camera to study the ozone layer.

It was understood by many that Commander Settle was highly motivated to bring the world altitude record back to U.S. soil and pushed the limits in order to achieve this goal. Unfortunately, ballast was deployed and most of the scientific instruments ended into the Delaware river in order to control the rate of descent. The Century of Progress was once again returned to the Piccards who flew it for its third and final voyage to the stars.

On October 23, 1934, a crowd of 45,000 watched the Century of Progress take it's third voyage out of Deerborn, Michigan to the stratosphere with husband/wife team of Dr. Jean Piccard and Dr. Jeannette Piccard. Jeannette who was the first licensed female NAA (National Aeronautics Association) balloon pilot in the U.S. Since Jean Piccard was still without his pilot's certificate, Jeannette received training from Ed Hill and became the first woman to pilot to the stratosphere.

Together they reached a height of 57,579 feet (17,550 meters). After noticing that the oxygen failed to vaporize on descent after the cabin doors were opened from previous flights, Dr. Jean Piccard created the liquid oxygen converter. This oxygen system was used on WWII aircraft. He also developed a frost-free window for the flight which was later used by the U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force in the B-24 Liberator or B-26 Marauder. Jean also discovered a use for blasting caps and TNT for releasing the balloon at launch and for remote release of external ballast from inside the sealed cabin. This was the first use of pyrotechnics for remote-controlled actuating devices in aircraft, an unpopular however revolutionary idea at the time. The instruments lost in the Delaware were replaced so that scientific studies could be conducted including studies on the use of atomic physics in conjunction with cosmic rays by Dr. Robert Millikan.

EXPLORER EXPEDITION

On October 23, 1924, Captain Albert W. Stevens (a US Army Air Corps photographer and discoverer) penned a six page proposal to his superiors during a trip to Northern Brazil as part of the Alexander Hamilton Rice Expedition. It was the first expedition to use aerial photography and shortwave radio for mapping. While under the directorship of Rice, the Institute for Geographical Exploration became a major center for the science of photogrammetry or map making from aerial photography. Stevens wrote his proposal from a tent along the Rio Branco near Boa Vista while surveying the Rio Negro as well as the Rio Branco. In his proposal, Stevens wrote to the USAAC (United States Army Air Corp) that the United States could be the first to attain the privilege of reaching the highest altitude…to the stratosphere. The flight mission was to collect scientific data on the composition of air, wind direction and velocity, temperature, pressure, cosmic rays, solar spectrum and the effects of altitude on radio transmissions. The USAAC agreed, but refused funding the project. Who would be able to fund such a mission?

Captain Stevens then contacted the National Geographic Society and requested they fund the balloon, gondola, instruments, and fuel while the manpower would be supplied by the USAAC. They, in turn, agreed. And so the NGS teamed up with the USAAC and began the journey to the stars with success.

This journey was not for the light hearted for it was a dangerous mission.

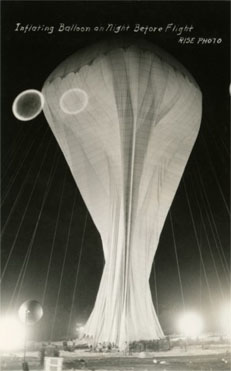

It began with a small gas balloon piloted by Major William Kepner and Captain Orville Anderson for a trial flight out of a 400’ deep limestone box canyon named the Stratosphere Bowl or “Stratobowl” for short on July 7, 1934.

This limestone bowl was carved by years of water in the Black Hills of South Dakota. The flight was successful and the Stratobowl provided a sheltered area below the rim which allowed calm wind conditions...perfect to inflate two of the largest gas balloons ever flown which would take most of the night to fill with the hydrogren used for Explorer I and the helium which was used for Explorer II. The Stratobowl is located just south of Rapid City, South Dakota.

The balloons needed to be enormous in order to carry a payload of over a ton of scientific instruments. The smaller of the two balloons was 3 million cubic feet and named Explorer I. It flew on July 28, 1934 to 60,000 feet above the earth, then the envelope separated until the friction of descent caused the hydrogen to finally explode. Explorer I crashed, destroying most of the remaining equipment onboard (scientific equipment was parachuted to safety in order to safe the data from space) while Major William Kepner, Captain Orville Anderson, and Captain Albert Stevens parachuted to safety.

An extensive interview was conducted after the crash of Explorer I to determine what was needed for a successful mission on the next balloon. It was concluded the balloon envelope needed to be larger, the gas needed to be non-combustable, the port hole on the gondola needed to be larger, and the payload needed to be lighter. So, an additional 700,000 cubic feet was added to the 3 million cubic foot Explorer II. Helium was traded for hydrogen and instead of a three man crew, Captains Orville Anderson and Albert Stevens were awarded the positions of pilot and science officer, with Captain Randolph Williams as ground operations.

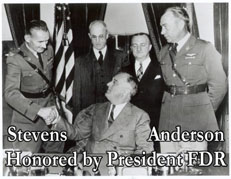

On July 11, 1935, the new improved Explorer II was ready for flight after a night of inflating the helium into the 3,700,000 cubic foot balloon. Unfortunately, a seam pulled apart and the flight was aborted. Over the next several months repairs were made and climatological data from the expected flight region determined the next attempt for launch should be in October. However, the weather window was not to open until November 11, 1935 in which the world altitude record of 72,395 feet (22,066 meters) was achieved. Space was conquered by Stevens and Anderson on this last mission to the stars.

From the Explorer Mission the first photograph of the stratosphere was taken almost 14 miles above earth’s surface. The flight mission collected scientific data on the composition of air, wind direction and velocity, temperature, pressure, cosmic rays, solar spectrum and the effects of altitude on radio transmissions. This data produced advances in the use of magnesium alloys, pressurization techniques, and personal equipment such as the heated flying suit.

The expedition learned much about the concentration of ozone, the ability for living organisms to survive exposure to stratospheric conditions, and unexpected changes in the radio waves we use to communicate to others. All of this later played an important part in giving American airmen superiority in the skies over Berlin and Tokyo.

ONE LAST CHANCE AT FLIGHT

On October 14, 1938 The Star of Poland was preparing to fly with the Polish crew of Captain Zbigniew Burznyski and Dr. Konstanty Jodko-Narkiewicz. Technical assistance was provided by Captain Albert Stevens of the successful Explorer Expedition, who traveled to Poland and Professor Auguste Piccard of Switzerland. Weather played a disasterous part with high winds and several attempts to fly. Around 4 AM the hydrogen filled balloon burst into flames from a witnessed spark on top of the stiff fabric buffeted by the winds. Fortunately, the balloon caught fire less than 100 feet above the ground and the gondola and persons on board were spared. This gave the Polish scientists hope for one last attempt to fly into the stratosphere.

In September 1939, the Polish team tried one last time to fly to the stars. Due to the explosive nature of hydrogen, the Americans supplied the team with helium. However, the German and Soviet attack on Poland made this final flight impossible as WWII was just beginning.

The final gas balloon attempt took place in June of 1940. The Soviet Union improved on safety devices and attempted to once again to launch a manned high-altitude balloon. However, the program was marked with accidents and failures and terminated after the Osoaviakhim-2 launch failure. And, so, the race for space was officially ended.

STRATOLAB

The 1961 Stratolab was an evolutionary stepping stone to space flight which retained the design of the Explorer gondola thus bridging the gap between pressurized capsule and the modern spacecraft helping bring about man's first walk on the moon 34 years after it was deemed an "impossibility".

We thank Captain Stevens for proposing and organizing a mission to space in collaboration with the US Army Air Corps and the National Geographic Society. His pursuit to rise to man’s highest altitude was successfully achieved along with Captain Armstrong, Captain Williams, Major Kepner who commanded the flight of Explorer I, and a host of almost 3,000 scientists, crew, and volunteers. They challenged the skies and succeeded. After a year long tour and numerous medals and honors to all three Aeronauts, World War II broke out and their accomplishments were quickly forgotten by the masses.

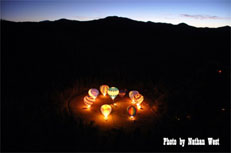

On September 24, 2010, after months of preparation and a special invitation by the local Tomovich landowners, the 75th Anniversary was celebrated at the Stratobowl by ten balloons piloted and crewed by a small group of hot air balloonists from 6 states who flew in order to recreate a tremendous achievement into the heavens. As the dawn slowly awoke, we stood in the freezing fog 400' below the Black Hills rim with a "peace" sign mowed into the 4 acre grassy field. With surviving members who witnessed the Explorer Mission, the surrounding public, as well as local media, the balloons lifted gently from the Stratobowl floor.

We were honored to fly from this historic site which to some was a great accomplishment, to others a chance to be a part of history, and to me a chance to feel closer to a grandfather I never met. A grandfather who stood in the Stratobowl, helping with the inflation of Explorer I and Explorer II, felt the lead pellets as they cascaded from the balloon and rose into the dawn sky, and who also became a part of history himself.

We take the time now to honor the Explorer Expedition of 1935 and their strength and accomplishment on November 11, 2010 on this their 75th Anniversary. Thanks to all who made my dream come true.

Flying from the Stratobowl

by Barbara Fricke

Plans were made for hot air balloons to fly from the Stratobowl to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the early space exploration flights from the site. The floor of the Stratobowl is privately owned by the Tomovick family. Kay West made arrangements with them for the balloons to fly from the bowl and to take Tomovick family members and friends for flights. This event was to be held the weekend before Fiesta. So, off to the Black Hills of South Dakota we go. But, what was I thinking?... A great trip and unprecedented chance to fly from the Stratobowl, and the America’s Challenge race is close at hand and I need some rest!

Nine of the invited balloonists and their crew arrived for this chance to fly from where history was made. The daily plans were for computer weathers briefings in the laundry room of the cabin resort where the pilots stayed. Then, a stop at the rim of the Stratobowl to set off pibals to check the forecast.

Finally, calls were made to Flight Service and the local National Weather Station in Rapid City where the local balloonists had an “in”. Flights out of the bowl would be great, if the direction was towards a recoverable areas.

The first day, Friday, the winds were forecasted to be light and variable with a general direction towards Rapid City, PERFECT! Being a newbie to the area, I decided to let Kay West lead the way and I would follow. A slow ascent out of the bowl with echos bouncing off the cliff walls sends an awesome feeling through you. She crested the rim and was off to follow Spring Creek valley for some orographic, or down valley drainage. Then up and over a ridge, noting the big horn sheep and wild turkeys on the ground. Down into a valley, over a golf course fairway, across the tee boxes and a stand up landing on a road with four other balloons.

What a great morning! The propane guy was in the bowl when we returned and offered us a price for propane that I had not seen in awhile. Pilots were paying their expenses on this trip, no sponsors were involved.

The second day was the same routine, but winds were a bit faster, and to a retrievable area. Hermosa was the town to fly to and off went the balloons with their passengers for another great day. Everyone got to the Hermosa area and had safe flights.

A glow was planned for Saturday evening. The crowd on the rim and in the bowl was unbelievable. The number of photo flashes uncountable. The paper printed a great photo and everyone involved had a good time. We are not usually glow people, but in the Stratobowl it was awesome.

Sunday, proved to be similar to Saturday in direction, but with lighter winds and the possibility of going to “no man’s land”. That did not happen, thank goodness. It took 1 ½ hrs to get close to where the balloons had landed the day before. Everyone had good flights, but one landowner was not happy and chased one balloon and crew off his rented land and gave a second balloon a really hard time. The balloonist chased off, Heather Day, returned after a safe landing elsewhere and had a long conversation with the “landowner” who had a previous bad experience with a balloonist some years before. After lots of sweet talking, the rancher’s feathers were smoothed over and his land is now balloon friendly.

It was a great experience and one I am happy to have been invited to take part in. We were told to take whiskey for the landowners, not champaigne, since whiskey is more appropriate for the ranchers.

Touring in the Black Hills was just as great as the flying. Mount Rushmore still stands and Crazy Horse is coming “alive”!